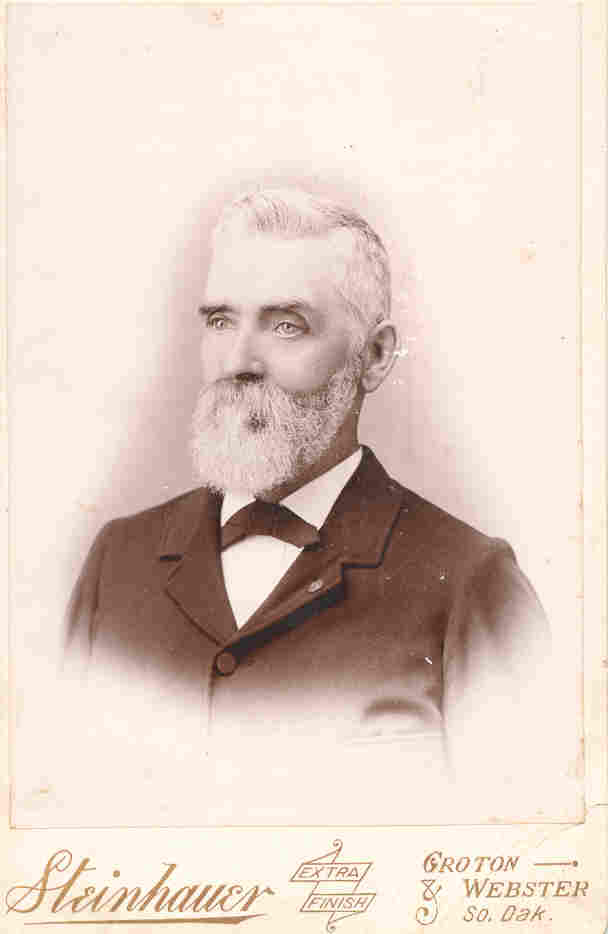

A Cowan Family Story - The following narrative was submitted by member Robert Cowan, who also supplied the picture and allowed us to reprint this here.

Webster, SD

September 1904

To My Dear Children,

I have often noticed how ignorant people generally are of the early

lives of their parents, previous to the time when they - the children -

were old enough to take notice of, and remember the various incidents

andcircumstances, which should make impressions of the minds and

characters of their parents. This I think is quite a loss to the

children. I have often wondered what my father's boyhood was, what

was his likes and dislikes, what company he kept, and what was his

occupation. But I only know that he was the youngest son, was raised

on a farm, and was his mother's pet. Neither do I know anything about

his young manhood, only that he was a Commercial Traveler, what the

Scotch called a packman. Often when thinking of these things, I have

thought that it might give you pleasure if some time I would write

you a short sketch of my life. My life, although I have had my cares

and sorrows, has been a very happy one THANK GOD.

Of course you know that I was born on the 21st of June 1834 at

Salford Manchester, in Lancashire, England. You also know of my father

and my mother who was a very good woman. Although not a member of any

church that I know of until I came to this country, when she united

with the Baptist church, she yet attended strictly to the religious

education of her children, taught them to pray, and insisted on their

regular attendance at Sunday school. Sunday school was an all day job

there. This she did so long as they were young, and until they took

upon themselves the ordering of their own ways. It is a blessed thing

to have a good mother, as I had, and as your had, and I wish and hope

its influence will be for the good of you children and children's

children.

At my earliest recollection - I think I was then about four years

of age - times were very hard. Trade was very dull, and although in

ordinary times we were in easy circumstances for working people, we

had to go to the public soup kitchen and very glad I was to get the

soup. I was then going to school and I could read. How long I had

gone to school I do not know for I don't recollect first going. I

suppose that I went about as soon as I could walk. I also went to

the Episcopal Sunday school. That was the time I first got a liking

for books. I think it came about in this way. The school gave prizes

or rewards to those children who at the afternoon session of school

could repeat the text of the forenoon sermon at church and give the

sense of the sermon. The reward was generally a little child's book.

Having a pretty good memory and being desirous to obtain the reward,

I almost always got it. From that time I began to collect books and

got a taste for reading.

My brother John was a block printer. This was before machine

printing was invented and all printing of cloth was done with wooden

blacks upon which the pattern was engraved. I don't know how it came

about, or why my parents allowed me, whether is was on account of hard

times or what, but at seven years of age I went to work with John as

his teerer. My work was to brush the color on the sieve every time he

put the block on it. As he had to put it on as often as he pressed it

on the block it kept me very steady at it. I don't think that I worked

very long at that time, as I had an accident, which laid my left

eyebrow open and that, finished me for that time.

Shortly after the time last mentioned we moved from Manchester

(we always called it Manchester although it was Salford, for

Manchester was the principal city and there was only the river which

is now the ship canal between) and went to a small village called

Ainsworth. Then I think began the happiest days of my childhood for

I was in the country. I always loved the country, even as a child.

I loved to wander off in the fields alone, gather wild flowers, listen

to the song of the birds, and seek their nests to become acquainted

with their habits. While we were in Ainsworth I went to school not

more than half the time. One reason was that we were about four miles

from school and another reason was that my mother was very much

troubled with rheumatism in her hands and feet, and for a long time

could not use her hands at all. I had to take care of the children

and do the house work under her direction. While there I had my first

religious experience. I was doing an errand for my mother, and on my

way home - it was twilight - and while yet about a quarter of a mile

from home, I was on a ridge and facing home. Looking up at the sky

when I seemed to see a large cross and on the cross the Savior. I

don't know how I knew that it was the Savior - it might have been

from pictures I had seen, but it was impressed on my mind that it

was the Christ and that my sins had helped to crucify Him. When I

got home I was crying and my mother asked me what was the matter.

I told her as well as I could and she soothed me telling me to be

a good boy, and say my prayers and God would forgive me.

I think we remained to Ainsworth about two years when we moved

to the city of Stockport. I went to school just about a week or two

and then went to work in the office of the factory as errand boy. I

got sixty cents a week. I think that we only remained in Stockport

about six months when we moved to Groton nearer Manchester. While

there I went to school about six months, and that was the end of my

schooling. I was then about eleven years of age so you see I did not

get much schooling. Why I was allowed to leave school I do not know,

I only know that I had my choice to go to school or go to work. That

was the way with all of us. There could be no idleness but my father

left it to us to decide. I have often thought it a pity that a

question of so much moment should be left to me to decide. I was of

studious habits, yet the idea of going to work and earning wages was

very tempting.

The first work I went at in Gorton was hooking in the making up

room, at Rylands Cotton Factory. Next I went to weighing copps in the

cop room, next I had charge of the factory store room, weighing and

counting out to the carious room bosses all of the repairs and

supplies needed in the factory. I had to book everything that I gave

out but I was not making money enough to satisfy me. Having a chance

to go to work as Carryeroff in making common or water bricks at the

brick works, I took advantage of it. I was very proud at week-end when

I took my wage home in gold instead of four or five shillings in

silver as I had been doing. Shortly we moved back to Manchester and

I went to work in the Corduroy room at Dewhursts Dye and Print Works.

I think I tended a machine there about a year and became dissatisfied

again. I don't remember just what was the cause of my dissatisfaction

but think that it was on account of profanity of the hands in that

room. I remember that something went wrong with my work and I thought

I would try to see if a good swear would relieve my feelings. I hardly

knew my own voice and felt so horribly ashamed of myself that I very

seldom used a profane word again. I then went to work in the blue dye

house where I worked until I went to Scotland.

Going to Scotland was another foolish, childish whim and it came about

this way. As I stated before, I had always been a great reader. Among

other books I had was The Tales of the Border, The Scottish Chiefs,

The Lady of the Lake and other Scottish works. As a natural

consequence I had an earnest longing to visit that country and see

for myself its lovely scenery, its castles and other ruins. I could

not think of any reason for going as that reason would have been

preposterous to my parents. They could not afford the expense of

sending me there to gratify my desire. None of my brothers or sisters,

not even my mother had up to this time visited that country but my

father's sister Agnes' husband (William Ceaser) was a shoemaker and

as my parents desired all of their children to learn a trade, I said

that I would like to be a shoemaker. It was the most senseless thing

I ever did for I know nothing about the trade. The confinement would

if I had ever given it a thought have been obnoxious to me and the

class of people that I would be thrown among more so.

As the saying is, it worked out all right and I went to Scotland.

I left home - the first of the family to do so - on the first of May

1847. My cousin Jessie Dunlop who was going home to visit her mother,

who was keeping house for my grandfather, accompanied me. We took the

rail to Liverpool and the steamer from there to Kirkcudbright, which

was the nearest seaport to grandfathers. Oh what a foolish boy I was,

but I did not know it then. It was a very pleasant voyage and we

landed at Kirkcudbright, and I found it so unlike any town or city

I had heretofore been in. There were no sidewalks, the streets, or

cassa went close up to the buildings, which were mostly low, and I

think thatched. We put up at an Inn kept by Mrs. Jolly the mother of

Jimmy Jolly who married my cousin Mary Ceaser. This Inn was one of

those q quaint, low, rambling, ramshackle buildings you have doubtless

often read about, and I don't doubt but John Paul Jones often

frequented it. We here met my Uncle Robert Murdoch who was smuggling

his son Sam out of the country, he having got into trouble with a

woman. We went from there to Borg where I visited Mrs. Smith, David

Bell's sister, and also Mary Jolly. Her husband ran the mill close

by, belonging to Smith. That was a fine country a round Borg, and

Smith's had a beautiful residence and fine country grounds.

We walked from there to Gatehouse on Fleet, and from there to my

grandfather's house. What a fine reception I got from my grandfather.

I did not understand or appreciate at that time how much my coming

meant to him, or how pleased he was to see me, but I do now. I was

the first of my father (Johnies) children that he had seen and I

understand the old man was then 97 years of age. He was quite active,

and with the exception of a slight deafness he enjoyed all of his

faculties. His complexion was fair, and he had red cheeks. I don't

remember that his hair was grey, he was not bald, and I think that

his hair was soft, thin and very light, something like Sennors. I

said he was very pleased to see me and enjoyed having me with him.

He was anxious all of the time that I was out of his sight, for the

house was not far from the sea shore and I was sure to be there

whenever the tide was out. My but I tell you that I was having the

time of my life. When we would be home he would draw a chair up

close to his and pat it with his hand and say to me, come here,

or he would take me out with him through the garden or orchard to

show me the trees. To me they were very old looking, and he would

say your uncle Jimmie helped me plant that, or if I remember right,

your father helped me plant that, and so we would go on. I had a

very pleasant time there, and the house in which grandfather lived

belonged to Sir David Maxwell. It was not far from the BIG HOUSE.

Grandfather had been with Sir David many years, and Sir David was

very much attached to him. So much so in fact that he would not

allow any of his family to care for him in any way, only Aunt Peg

his oldest daughter kept house for him.

But all things have an end, and so did my visit to grandfathers,

and we went from there to Gate-house-on Fleet and made a visit to

Uncle Robert Murdock, who afterwards took us in his Irish car to

Castle Douglass. From which place we went by carrier's cart, on the

top of barrels of whiskey, to Dumfries, and from there on foot to

Amisfield the house of bondage.

May 25th, 1905

It is several months since I wrote anything in this. I have been

to Illinois and lots of things have happened, but about them

hereafter. I will say now however, that since I returned from

Illinois I have been in correspondence with John Cowan of Langholm,

Dumfrieshire, Scotland. I desire to find out who was the father of

my great-grandfather Joseph Cowan. He answered by giving his genealogy

so far as he knew it. He says that his great great grandfather Robert

Cowan was born about 1702 or 1705 at a place between Locherby and

Lochmaben, the exact spot is not known. Also that the said Robert

had two sons: James - his grandfather - and Joseph. Now the said

Joseph could not be my great grandfather for he was born in 1710

but he may have been a brother. I am still corresponding with the

said John and have sent him some money to help defray any expenses

he may be put to in his investigations.

Well I stated that I arrived at Amisfieldtown, the place where my

Uncle William Ceasar, under whom I was going to learn to be a

shoemaker lived. As to the reception that I received from he and

his family, I cannot say much for I do not recollect it. But the

impression I have and I believe it to be true is that they were

disappointed. I was very small for my age, but healthy and sturdy.

They had evidently expected a large, stout boy. Oh there was no

sentiment about them, it was all business. They took apprentices

for what money they could make out of them, for they were expected

to serve five years, and all they received was their board, oatmeal

porridge and night and for dinner just what they could catch. Only

six weeks time in harvest to earn money to but their clothes. I

never received any evidence of affection from them, but was always

made to feel I was OUTSIDE. With uncle David Bell and his family it

was very different, they always treated me kindly, and in many ways

showed their regard and affection for me. Aunt Jean Bell was a very

kind, motherly woman. I got along fairly well at Ceasars, and we

never had any trouble to amount to anything, that is, we never had

any words. I can say that I worked faithfully, and tried to learn

all I could about the trade, so far as they would give me an

opportunity to do so.

I only tried to hire out for the harvest once, that if I remember

right was the third year I was there. That time I went to Locherby

Lamb Fair, which was held in August, and was the last hiring market

before harvest. Well, there I was going around amongst the folks in

the market with a straw in my mouth as the custom was with those who

wanted to hire out. But not a bid did I get. I suppose that I was too

little, and I suppose I looked pale and different to the natives. I

don't think that I was very much disappointed. I had plenty of

clothes, my parents saw to that, and I got sixpence in every letter

I received from home. But everything has an end, and after having

been there over four years I went home on a visit and did not go

back again, although I fully intended to when I left. No doubt you

will wonder that I stayed there so long, I have wondered myself

sometimes why I did. But it was the best thing to do and the

experience I got did me lasting good. I had lots of books to read

and study in my spare time and on Sundays or the conditions would

have been intolerable. I took one year to the reading and studying

of Rollins Ancient History together with the Book of the Prophet

Isaiah. That did me lasting good, and I would advise each of you

to do the same, and you will never regret it.

While in Scotland I went to singing school one term - that was

in the winter. There singing and dancing schools were always held

in the winter, in those days, and I presume yet. The winter days

are short and the young folks can get the evening for instructions.

Perhaps I did not derive much benefit from the signing school, but

I know that I was very much benefited by the two winters I spent at

the dancing school, for I was a very awkward, ungainly, shambling

boy before I went and perhaps being in the company of girls caused

me to carry myself more erect, and to walk as a man ought to walk.

Now there was nothing very remarkable happened to me while in

Scotland. I fell in love as most boys do in their calf days, but I

was kept clean of vice for which I am very thankful. I went home on

a visit, fully intending to go back, but after I was all ready

determined to stay at home for a while, and so bade good bye

Scotland.

When I went home from Scotland I went by rail from Dumfries to

Anaan and took a steamer from there to Liverpool, going close by

Whitehaven where Paul Jones landed during the Revolutionary War;

and around St. Bees Head a rugged corner of the coast where the

waves dash and toss and turmoil nearly all the time I think. That

is a very rough coast and appeared to be perpendicular and from ten

to fifteen hundred feet high. I got to Liverpool about three o'clock

in the morning. This I think was in June when there is very little

night and thought the sun was not risen yet it was good daylight and

was quite chilly. I had remained on deck all through the passage,

for the people in the cabin were most all seasick, and the sight of

them and the smell of the whiskey they had drunk was like to make me

sick I therefore remained on the deck. On my way from the dick to

the railroad station through the almost deserted streets, but which

were just beginning to wake up a little, in passing under a railroad

bridge (the railroads there run over the top of the buildings), a man

was just setting up his coffee stand, Now I had not smelled coffee

since I had left home years before, and I was hungry so I got me

coffee and buns. Never anything tasted so good to me. It makes me

feel good today, as I never get coffee that smells as good, and

tastes as good as that did.

I arrived at Manchester about eight a. m. and met my dear mother

once more. My but it was good to be home again. The family were well

at this time but they had gone through a siege of scarlet fever only

a short time before and my little sister Jean had died. That made

three less in the family than when I left home for Will first went

to the United State, America we called it, then Richard went. Then

John got married and Jean died. Yes that made four less at home. Well

I decided that I had enough of Scotland, and thought that my parents

needed what help I could give them, therefore I started out to hunt

for work (at my trade). I got it, piecework, that is the way the

journeymen worked, so much a pair. But I could only stand it a short

time, for the men were a rough drinking lot and that was company I

never could endure. It appeared to me to be a characteristic of that

trade generally, so I quit it and got work in the Print and Dye Works

where my father and brother John were employed. Business was very

good at that time and I made a day and a half overtime every week

and also did some work at my trade at home, morning and nights. My

time was very fully employed, Sundays as well from 9 a.m. until

sometimes 10 p.m. with Sunday school and Chapel work. That was the

way I labored and spent my time until the summer of 1853 when I made

up my mind to go to America for I could see nothing good ahead of me

there. My parents were getting old, their health was not good and I

thought that if I came here I could earn more money and could get a

piece of land for my father. So on the eighteenth day of August 1853

I left Liverpool on the ship Benjamin Adams; one of 750 passengers.

It took us about two weeks to get out of the English Channel. We

had a terrible rough time of it and on the 10th of September we had

a three-day storm during which the steerage passengers were under

hatches, in darkness, without food and water. We lost our topgallant

and royal masts, our jib, and all our sails (every yard), and all of

our boats except one small one. We had a load of railroad iron and

that shifted and stove in many of our water casks. We were put on

short rations of food and water during the rest of the voyage. We

were eight weeks and four days I think in making the passage over

but life went on just the same. We had several births on the vessel

and some deaths. I enjoyed myself very much. I found a plenty to do.

There were lots of people who needed help that I could give and they

got it and we both profited thereby. The many years subsequent to

that time have shown to me time and again that it is well to be

employed at something, even though you get no returns in money. You

will certainly receive a recompense.

On landing at New York I fell among thieves (sharpers). How it was

done I don't know but I think it was in exchanging English money for

United States, but they got it. I had but little more than enough to

take me to Buffalo. I took steamer to Albany up the Hudson, then went

by rail to Buffalo. I very soon found David Bell's Engine Works and

received from he and his wife a very cordial welcome. They took me

into their home and treated me as a son. David wanted me to remain

with him and he would give me the best education the city would

afford and he would teach me the business. But I considered my duty

to my parents required me to go west and try to make a home for them.

So after staying in Buffalo two weeks, David gave me transportation

to Morris, Illinois and said that after I had got out west and given

farming a trail if I didn't like it to go back to him and he would

do as he said. He was just as kind as he could be and I will say now

that I have been treated more kindly by the Bell family always, than

by any other of my relatives. While I was at Buffalo I called on

Munich's, she was Jean Bell, and the Campbell's and Byers but I had

known them in Scotland.

And so I started for Morris, Illinois. I went to Detroit and then

by the Lake Shore to Chicago and then by Rock Island RR to Morris

arriving there about three o'clock on Sunday morning. About the

middle of November1853. I now had to get out in the country, 7 miles

north of my brother, Dick's. After making night hideous for some of

the people in Morris, I succeeded in getting them out of bed and got

from them the necessary directions to take me to Dick. Dick was

married then. John was the baby. Dick and Crowthers were living

together on 40 acres in Nettle Creek. Now just imagine me in the

wild west on a cold bright Sunday morning (although the stars were

shining yet), dressed in black broadcloth, a silk hat, black kid

gloves and a cane (the best clothes I had ever had, have had none

as good since) walking along the mud roads on that early Sunday

morning. I was hungry too.

Well after walking about four miles, I passes a house and the farm

was fenced with a post and rail fence. On the other side of the fence

was a cornfield. Everything was quiet. I looked closely around to see

if anyone observed me and not seeing anyone I dodged between the rails

into the cornfield. I jerked off three ears and scrambled back onto

the road and undertook to stay my hunger. The corn was soft, that

was all right, and it was black. Well thinks I, if this is what they

eat here, I'm going back. But I kept on and after a while arrived at

Dick's. The house was about twenty rods from the road. Mrs. Crowther

saw me as I approached the house and she said, "Dick, Dick the

preacher's coming." Dick came around the house and met me as I got

to the front. He said, "How do you do, sir." He didn't know me so I

had to make myself known. He took me into the house and introduced

me. They got me breakfast and it wasn't corn. Dick had been dressing

a little pig they were going to bake for dinner and they did not want

the preacher to see them at it. But I made a hearty dinner of it just

the same. I never wore the silk hat again and soon outgrew my black

clothes. My black kids were replaced with buckskins and the cane,

well I've got a few now but never use them for I don't like the style

any more.

That winter my brother Will and I husked corn. There was some corn

but it was very light stuff and I worked at my trade a short time with

McCady at Lisbon. That year they had a killing frost August 18. I had

not noticed before that it was the very date I had set sail from

Liverpool.

Now I went to farming for the first time. I hired out to Joseph

Bushnell for a year at $12 a month and began work on the first of

March. I started in with the determination to do as much work as I

could and as well as I could for I had no intention of being a hired

man very long. On March first 1855 I drew my wage of $142.75. I had

drawn $1.25 before for Uncle Will to pay his tax. The rest of the

money I sent to my father. On that said first of March I began to

work for John Bushnell at fifteen dollars a month.

You have never known and probably never will know the loneliness

of a person who is a stranger in a strange land, how they are made

to feel that they are outsiders. Even the churches take little if

any interest in them. I was made to feel that I was regarded as a

green Englishman and that I wasn't supposed to know much.

Bushnells was a station on the underground railroad and several

negroes were hid away in the daytime and carried away to the next

station north in the night. I had nothing to do with that although

I was an abolitionist. I had read Uncle Tom's Cabin years before in

England, I think before it was published in the United States. But

then England had abolished slavery in the Provinces years before

and the English were generally anti-slavery. I don't believe that

I would be an abolitionist now and I doubt if the freeing of the

Negroes had been of general benefit to them as a national policy.

I think that emancipation was bad for it had never been known that

two peoples of alien race could dwell in the same country in harmony.

One must rule and the other be subject. Our country ought to be kept

as a white man's country. The Germans, British, Irish, Scandinavian,

in fact nearly all of Europe are of the same race and although of

different nations and language they assimilate, mix and make a

distinct type that we may call the U. S. of American type of men.

But to allow the free emigration of Negroes, Mongolians, Japanese,

Hindues shat kind of condition would prevail, what kind of a people

would we become.

My mother died in the summer of 1854. If I thought that I would

not see her again in this life, I would not have left her. In July

of 1855 my father, Matilda, Ben, Agnes and Mary came to Illinois.

In the fall of that year I took John Bushnell's corn to husk and

had the use of the house and buildings and father and Aunt Matilda

kept house for me. Nina Rolla was born in that house. I also bought

a team from J. B. for $300 and Tom Allan and I bought a threshing

machine for $350. The next spring I rented Uncle Will's farm (he

had married) and bought 160 acres on contract. I went to housekeeping

with the girls keeping house for me. So you see how I went into debt.

It was all right too if I had only had someone to advise me. I can

see now that it was all right and it would have come out all right

if I had kept the land, but crops (wheat) began to fail, hard times

came on, and interest two and three per cent a month. I was loaded

down with debt.

In 1856 I began farming for myself, corn and oats. It was a wet

spring and the land was low wet land. My oat crop was good. I got

two thirds but the price was so low that they did not pay expenses.

The corn was not a very good price either. That fall I rented a farm

from S. P. Bushnell and put in 25 acres of winter wheat. I paid a

dollar twenty-five cents a bushel for the seed. I was married on

the 20th of November of that year and we moved onto the Bushnell

farm. Thinking there was more land than I could well work myself,

I let T. Allan have some of it. He was married three weeks before

we were, and they occupied a part of the house. That was a bad

mistake.

That fall the Republicans nominated their first ticket and

Fremont and Payton were the nominees for president and Vice

President. The next year winter wheat turned out to be cheap.

I had not much coming in. Interest was 24%. Our first child,

Isabella, was born on the 3rd of August that same year.

In 1858 I put in 25 acres of spring wheat and several acres

of oats, 15 acres of corn. I sent to New York for 100 lbs. of Guiana

and used it on the corn. In October (I think it was of this year) I

took a trip to Ottawa to hear the Lincoln-Douglas debate. I doubt if

any thought as they heard Lincoln that they were listening to one of

the greatest men the world ever produced. I know I didn't.

22 November 1912

The longer I put off doing anything the more I hate to do it. I

have only brought my life up to 1858 and that is 54 years back.

Whether I will succeed in bringing it to date I know not.

In January 1859 I broke my right foot at the instep and about

March first I was taken sick with scarlet fever. My father was now

living with us and Agnes and Matilda were at the house making comforts

for his bed from some curtains that had been folded and put away after

they had had the scarlet fever in England. We did not know anything

about disinfecting in those days so you will imagine that when I was

over the fever I was in very poor condition to begin a season's work.

Too my foot was still lame. But stern necessity was the driver not.

I had lost my crops two years running and was now paying three percent

a month on my debts. My failure hereto had been in wheat and oat

crops. I determined to put in a big acreage of corn but I also put

in 15 acres of spring wheat. We did not have any corn planters or

double cultivators in those days so that planting by hand and

cultivating 53 acres of corn was a big undertaking, but I did it.

I was determined to get out of debt or founder. I didn't wait for

daylight in the morning, but got up by the morning star and dawn

found me in the field and often 9 and 10 o'clock at night. Well

that year was my first experience with chinch bugs. The hurt the

wheat bad and took three acres of the corn but I raised a good crop

of corn. That spring we had a killing frost on the fifth of June.

Jean was born on the 13th of August that year and my father died

on the 30th of September following. That fall I rented a farm from

Sam Packwood between Odell and Cavuga in Livingston County and we

moved there that winter. This farm was all new ground breaking.

None of it had been plowed and some of it had gone back tow or

three years. But I got along fine and planted 75 acres of corn.

After corn planting I got hurt. A horse fell on me and crushed my

chest so that I was unable to do any corn cultivating. I hired a

man for a month and the land being new I raised a fair crop of corn.

But the wild cat banks now began to go down and values began to go

down. Early in the fall I sold 300 bushels of corn at 25 cents a

bushel, then 299 at 20 cents and it came down that winter to 10

cents a bushel. The nation was all torn up and it appeared as if

everything was going to ruin.

(End of record as found)